After learning about GBV, we’re now going to start our discussion on what are Victims’ Rights.

Again if at any time you feel uncomfortable, there are strong emotions, please stop the video and ask someone in your group to lead a self-care exercise. Remember we will learn about 10 Lessons.

Lesson 1: Women Victims have Rights to Truth, Justice, Healing and to live Free from Violence

- We have learned about the rules that say you cannot commit gender-based violence. These rules can come from domestic laws of specific countries, like Myanmar and Bangladesh. There are also international law that countries must respect.

- Based on these rules, women victims of GBV have rights.

- They have the right to know the truth about what happened to them

- The right to justice, to see perpetrators brought to court and punished,

- The right to heal their lives through reparations,

- and the right to never again have to live those experiences of violence

- These rights are set out in the UN Principles on Victims’ Rights to Remedy and Reparations and was adopted by the U.N. General Assembly in 2005.

- Women from many conflicts in Asia continue to work for their rights for decades. It is a long and difficult road.

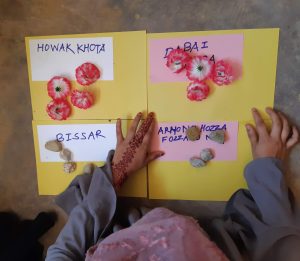

- Remember, we used the Stone and Flower activity to discuss victims’ rights to truth, justice, healing and to live free from violence.

Lesson 2: Women Victims have the Right to Truth

- The Right to Truth means that women victims of human rights violations, their families, and society have the right to know the truth about what happened.

- Women victims have the right to know about the events, the context and conditions, the reasons, and the people who participated in these violations.

- In the case of people who have disappeared or who have been killed secretly, the right to truth includes to know the fate and whereabouts of the victim.

- This is a photo of a woman in Aceh, still searching for her husband many years since he disappeared.

Lesson 3: Women survivors need safe spaces and support to speak out about their experiences and needs

- Because of their feelings of fear and shame, women often do not speak out about their experiences of sexual violence. Their families often pressure them to stay silent.

- In efforts to document human rights violations, women are often overlooked.

- However, women survivors need to be empowered so that they can begin to speak out about what happened to them, and to bring attention to their immediate and long-term needs.

- Women survivors and their advocates need to understand the root causes of such violence to avoid repetition in the future.

Francesca, a lawyer from the Philippines has worked with women survivors.Let’s listen to some of her experiences: When we talk about truth, women own half the truth. Half of the people involved in conflict situations are women so we should recognise their roles not just as victims but as leaders in conflict situations.

Lesson 4: Women Victims have the Right to Justice

- Victims have the right to justice. This means bringing perpetrators to court.

- In this process, judicial actors will look for evidence about the crimes, they will try to prove guilt or innocence in a court, and a judge will decide if they are guilty or innocent. If they are guilty, they will be punished, for example by being sent to jail.

- Criminal prosecutions focus on individual criminal responsibility. It means that if someone commits a crime, they will be punished personally. It’s different from the responsibility of the the government.

Lesson 5: There are many barriers to women accessing justice

- States (which means, governments) have the first responsibility to prosecute and punish serious crimes.

- At the national level, the options include the civilian criminal courts and the military courts But these often are not done in a transparent way.

- It is also possible to create special courts or special units within the existing justice system. But this needs special resources and political will.

- If States don’t prosecute in their domestic courts, there are options at the international level.

- For example, in the 1990s, international tribunals were established for a specific situation for Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

- Since 2001, the International Criminal Court, called ICC has been established. But the ICC can only reach countries that have signed-up to be part of the ICC (as the case of Bangladesh). Or, a UN Security Council decision can refer a case to the ICC, but this is very rare.

- In some instances, mixed or hybrid courts can be used, which means there are some national and international components, like we have seen in Cambodia and Timor-Leste.

- However, all over the world, only a very small number of victims of GBV can ever get some justice through the courts.

Francesca: A lot of the violations of course occur to women and in most areas they are not empowered enough to seek for justice or redress, or maybe they feel like it was their fault, or they are not entitled to any justice because of some cultural difference like women should have been left at home or if they had decided to go out of their home unaccompanied by a man, then whatever happens to them would be their fault. Things like that…

Lesson 6: Women Victims have the Right to Heal through Reparations

- The goal of reparations is to recognize and address the harm suffered by victims, to try to eliminate the consequences of the crime, in order to restore the dignity of victims. We try to address the needs that are moral, physical, psychological and social.

- There are different kinds of reparations. They can be material or symbolic.

- Material reparations are concrete forms of assistance to victims. It can be compensation, some kind of a financial payment for damages.

- It can also be something called rehabilitation. That means some kind of services including education, mental and physical health, legal aid, and economic assistance.

- Materials reparations can also include restitution: returning victims to their original situation as much as possible: getting back their employment, full citizenship, the return of stolen property, or the repair of damaged property.

- The idea is to try to help improve victims’ lives, so that they can get back on their feet.

Lesson 7: Victims of GBV have the right to heal and to be empowered

- There can also be symbolic reparations. Symbolic reparations try to provide victims with a moral satisfaction and to restore their dignity.

- This can include apologies to victims from those responsible for the violations, monuments dedicated to victims, days of remembrance and renaming public places, etc.

- We need to think carefully about how to do reparations for crimes of sexual and gender-based violence.

- The type of crimes happens because of a pre-existing situation of inequality and discrimination against women. So, we need to make sure that reparations don’t reinforce the injustice that existed before. On the contrary, it needs to change it.

- We say that reparations need to transform the situation. Reparations programs need to be transformative.

Francesca: It’s difficult to give an exact value to what a woman loses when she’s in conflict situations. She not just loses money, property, time with her family, a lot of reproductive rights, sexual rights, but also a chance to be herself and to be a better person for her community, and we can’t put value to that. So it’s not something we can just replace with money.

Lesson 8: Governments must promise not to repeat violence, so victims can live free from violence

- To finish, let’s look at the last victims’ right, which is the right to be free from violence.

- We call this guarantee or promise that the violence is not repeated.

- This means following a period of conflict governments are required to ensure that these violations , these violences never happen again.

- There needs to be reform in the laws (like the constitution, criminal law), in the judicial system (including judges, lawyers, and all the procedures), in the security sector (police, military), and also of the education system, the media, etc.

- Reform is needed to ensure that institutions are accountable for their actions, that they are democratically controlled, and that they respect the rule of law and human rights.

- One of the most important elements is that we need to make sure that military and the security forces are controlled by a civilian government. This is always a key in preventing reoccurrence of violations.

Lesson 9: Women victims have the right to live free from Violence

- We need to pay special attention to addressing sexual and gender-based violence as part of reforming the justice and security sectors.

- For example, we need a vetting of people in the army, in order to disqualify or exclude some of the people who committed the crimes and the violence in their position.

- It is also important to ensure gender representation in the police and in the army, in particular that women are involved in good senior positions and that they are involved in decision-making processes.

- Reforms must be used not only to restore victims’ rights, but also to change the situations of gender discrimination and inequalities between men and women.

- Changing the laws, creating new ones, is crucial in ensuring that the root causes of violence do not lead to renewed violations.

- This often includes changing the Constitution, but also may include laws to protect women’s rights, victims’ rights, citizenship rights, etc.

- It is important that domestic laws are brought in line with international human rights standards.

Francesca: When we talk about institutional reforms, maybe we should put more women in governments. So one of the ways to do that would be to teach the women, to train them that they do own half the world and they should take more active roles making sure that we carry half of the world as well.

Lesson 10: Women victims’ participation is key to achieving lasting peace & justice

Women survivors need long-term strategies to empower themselves, working with NGOs, so that they can fully participate in the long journey for justice, healing themselves, their families and their community.